**The Veil of Reason**

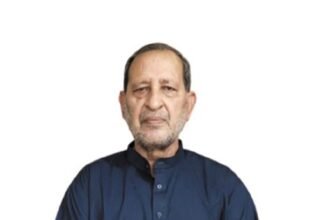

Roedad Khan was one of Pakistan’s top bureaucrats. Born in Mardan, he joined the civil service in 1949 and served in all key positions across the country. He was highly educated, shrewd, and charismatic. He passed away on April 21, 2024, at the age of 100. During the tumultuous year of 1971, when Pakistan was on the brink of disintegration, he was serving as the Federal Secretary of Information. He met with President Yahya Khan and his close circle almost daily, and Roedad himself drafted the announcement of East Pakistan’s surrender and the disintegration of the country. I had the opportunity to meet him several times after the year 2000, including during his final years.

Even in his last days, he maintained a distinguished appearance, always wearing a clean, well-tailored suit with polished shoes. However, he struggled with speech; words would get stuck on his tongue, and he had to exert effort to articulate them. Despite this, his memory was remarkably sharp—he could recount events from World War II, share stories of the corruption of Nawaz Sharif and Asif Ali Zardari, and narrate the blunders of General Musharraf and Imran Khan. In his final days, he was deeply disillusioned with Imran Khan.

He would often remark that fate had given Imran Khan a golden opportunity to transform Pakistan, but he had squandered it miserably. He was the first politician in Pakistan’s history to have strong support from the military, which he could have leveraged to set the country on the right course. Instead, he surrounded himself with foolish advisors, and together, they drove the nation to ruin. Roedad would often share untold stories about the 1971 tragedy.

He would say that while East Pakistan’s separation from the West was inevitable, no one had anticipated it happening in such a horrifying manner, nor imagined that it would leave Pakistan with the burden of a war’s defeat around its neck. When the news of East Pakistan’s separation came, there wasn’t a single person in the country who wasn’t in tears, and the nation was engulfed in sorrow. People were weeping in the streets, and that wound still scars our generation’s collective consciousness. I asked him, “Sir, in 1970, the country had hundreds of wise, experienced, and intelligent people like you. The military also had smart and brave individuals. Despite his drinking and indulgence, General Yahya Khan was considered a brilliant general, with no accusations of financial corruption against him. Even his junior officers included devout, five-time-prayer generals filled with the passion for martyrdom. Yet, the 1971 tragedy unfolded before you all, and you watched in silence. Did no one have the sense to step in, bring Yahya Khan, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto to the negotiating table, and dismantle the walls of mistrust between them?”

“When General Yahya Khan decided to launch a military operation in East Pakistan, was there not a single general who could have warned him of the catastrophic consequences? Or when Zulfikar Ali Bhutto declared at the Minar-e-Pakistan that he would break the legs of any of his MNAs who went to Dhaka (at the time, the National Assembly was located in Dhaka while the federal government was in Islamabad), was there not a single sensible politician, businessman, or bureaucrat in the entire country who could have convinced Sheikh Mujibur Rahman? If you had acted back then, perhaps Pakistan could have been saved from disintegration. Your small efforts might have saved our 92,000 soldiers and civilians from Indian prisons, spared our army from the disgrace of surrendering at Paltan Maidan, and prevented the wall of hatred from being built between Bangladesh and Pakistan. Even if we had parted ways, we could have remained as brothers.”

After listening to my lengthy question, Roedad Khan let out a deep sigh and replied, “We retired people have been asking each other this question for the past fifty years. Even this morning, I was asking myself, ‘Roedad, the country was falling apart before your eyes, and you were busy protecting your job. People were dying in East Pakistan while you were spreading false news through Radio Pakistan, Pakistan Television, and the newspapers. You were deceiving your people and yourself. What face will you show to God?’ Every day, I present myself before the court of my conscience, and I find no argument in my defense. Sometimes, I feel as though fate had perhaps locked our reasoning at that time. It had stripped us of our ability to think, understand, and act. We could see, but we were blind; we could hear, but we were deaf, and thus, the real Pakistan separated from us.”

He paused, took a deep breath, and continued, “We, the West Pakistanis, did not create Pakistan. Punjab, Frontier, Sindh, and Balochistan did not play a significant role in its formation. Lahore’s only contribution was hosting the Lahore Resolution at Minto Park. We were all beneficiaries of Pakistan. The true credit goes to the Bengalis. They founded the Muslim League, made financial, social, and personal sacrifices for the country, and were morally, socially, and academically superior to us. They also outnumbered us. For the first time in history, a majority decided to separate from a minority, ran a movement against the minority, and the minority launched a military operation against the majority. Today, I feel that the Bengalis did the right thing by parting ways with us, for otherwise, even now, they would have been mired in sit-ins or under martial law.”

Roedad Khan’s words left me shaken. These were the reflections of a 100-year-old man who had lived a distinguished life and witnessed the most critical events in the country’s history. He was no longer entangled in the pursuit of life, knowing that today or tomorrow, the thread of life would slip from his grasp. Therefore, his analysis of the past was candid and valuable. He would often say that when fate wishes to destroy a nation, it clouds the reasoning of its rulers, stripping them of the ability to understand and act. This is what happened in 1971, and it is happening again in 2024. The country is once again entangled in a complex triad. Imran Khan, from his jail cell, is weakening the nation’s foundations.

God had given him power and the unconditional support of the military, yet he failed to manage either. Despite all his blunders, the people still stand with him. He had overwhelming public support in the February 8 election, but due to his stubborn and inflexible nature, he squandered it. He has now become the 2024 version of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, while the Pakistan Muslim League and Pakistan People’s Party are like the Zulfikar Ali Bhutto of 1971. They know the people have rejected them in the election and that power is not their rightful claim, yet they cling to the throne, willing to pay any price for it.

They lost the moral high ground long ago and are now also devoid of the ability to recognize the truth. They know this is the last term for the Sharif family, and no one knows where or how they will be afterward. The next prime minister will be Bilawal Bhutto—why? Because Pakistan now needs a Sindhi prime minister who is also acceptable to Iran, and Bilawal is a highly suitable candidate for this role and is prepared to pay any price for it. On the other hand, the establishment has decided that no negotiations will be held with Imran Khan, no matter what he does. They are also willing to pay the price for this decision. Hence, the country stands at a crossroads once more, with no path forward or backward, while all our problems can be resolved with just a little flexibility.

We all need to take a step back, and things will start to improve. Imran Khan should stop issuing unnecessary calls for protests and allow his party’s political committee to negotiate with the government, or else mandate Maulana Fazlur Rehman and Mehmood Achakzai for the negotiations. Nawaz Sharif and Asif Ali Zardari should also make some sacrifices, agreeing to a two-and-a-half-year term instead of five years, engage in a grand political dialogue, and make all the necessary constitutional amendments at once. Lock the constitution thereafter and hold elections in two years, allowing the winner to take power. The establishment should also create room for political space, and the judiciary should step aside for a bit. This entire crisis could be resolved within a week; otherwise, the turmoil will devour countless lives and the last remnants of the nation’s honor. Fifteen years from now, today’s Roedad Khans will also be lamenting, saying, ‘God had deprived us of our senses too; the country was falling apart before our eyes, and we remained silent. We too had lost our minds.'”