Chemicals Ka Locha

Mano Bhai was an exceptional columnist who used to write under the title “Girebaan,” and with the chisel of his words, he would tear apart many collars. In one of his columns, Mano Bhai humorously narrated the story of a Major’s horse and its fate, writing, “After kicking three sergeants and four lieutenants, the Major’s horse delivered its final kick to the bomb.”

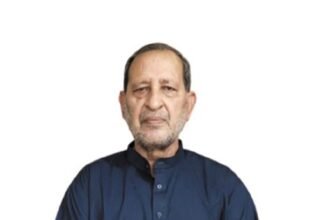

Looking at Dr. Zakir Naik reminds me of that horse and its final kick. Naik spent his life kicking the religious sergeants of Hinduism in India and the lieutenants of the Church in Europe through debates, and now, with his visit to Pakistan, he has delivered his final kick to the bomb.

Dr. Zakir Naik spent his entire life debating with non-Muslims and answering their questions. He rarely encountered the Muslims whom he used to urge non-Muslims in Europe to emulate. Most of his sessions took place in Europe, India, and other places where his audience was largely non-Muslim. There, he could easily recite memorized chapters from the Bible in fluent English and get by. Even if questions arose, they were usually about comparative religion, after which the questioner would often convert, much like the devotees of mystics who would eventually recite the Islamic creed.

However, this time, Dr. Zakir Naik has come to the heartland of Islam. Since the era of Zia-ul-Haq, the center of Islam has seemingly shifted from Hejaz to here, where we have become “more Muslim” than the Arabs, or as Yousufi would put it, we have gone somewhat mad. Instead of being merely religious, we are lovers of the faith, and in love, there is a kind of madness. Religious love is an escape from institutionalized religion, which demands discipline. People who tire of discipline often take the path of love.

This path of love is a delicate matter. Either those fleeing the constraints of institutionalized religion seek refuge in mysticism, becoming figures like Baba Bulleh Shah, Mansur Al-Hallaj, or Bayazid Bastami, or if the “chemicals of love” fluctuate even slightly, a chemical imbalance occurs. It’s the same kind of imbalance Sanjay Dutt experiences in the movie “Lage Raho Munna Bhai,” where thinking too much about Gandhi causes him to start seeing imaginary visions of Gandhi everywhere, mistaking them for reality.

This very chemical imbalance produces figures like Ghazi Ilm-ud-Din and Mumtaz Qadri. Even if prophets and avatars were to come and clarify that what their followers are doing is not part of their teachings, the afflicted would still claim, “You are wrong; we are right.”

Dr. Zakir Naik has come to a country filled with Muslims who are suffering from this kind of “chemical imbalance.” He spent his life preaching Islam in English to infidels, but when faced with real and born Muslims, he seems to be at a loss. Just as a dancer thrives on stage, the preacher’s memorized Bible verses and scriptural quotations have started to lose their shine among his fellow believers.

Blunders are becoming a frequent occurrence.

The scenario of “brother, sister, ask a good question” worked well in the lands of the non-believers, where one could sell the idea that “to see Islam, don’t look at today’s Muslims. No matter how good a car is, if the driver is bad, the car will crash. It’s not the car’s fault, but the driver’s.”

However, religion is not a car. Religion is more evident in habits than in books. It isn’t just a philosophy to be framed and kept in books; if it fails to permeate the behaviors of nations, then the fault lies not only with the driver but also with the vehicle.

Now, if you avoid placing a compassionate hand on the heads of young girls because they are considered non-mahram, who taught you this way of thinking?

How can you invite a non-Muslim woman to Islam while referring to single women as “public property” and simultaneously claim that Islam is the guarantor of women’s rights?

The “chemical imbalance” is particularly prevalent in the religious fabric of the Indian subcontinent. Its layers keep peeling off according to the demands of the time, just as they are now peeling off for the good doctor.